- Jhilam Roy

Why do they need the fingertips naked?

They may dip it in any stranger’s blood.

This city which was a banquet of beautiful

people—

This city which was the foundation of many a

fresh sapling.

This city which was a gathering of the

moon-like beauties,

This city which was a quarter of the

possessors of charm.

This is the very ground that would throw up

gold.

This is the very dust where from we find elixir.

[Zahir Dehlvi, Daastan-e-Ghadar]

It’s oft said that no city is a mere space but a cornucopia of

wordless and priceless emotions. It speaks, it jubilates, it hurts, it heals.

Yet, as John Updike says, ‘Cities aren’t like people. They live on and on, even

though their reason for being where they are has gone down-river and out to

sea’. Indeed, cities are synonymous with infinity, an ever-shifting, endless

battle-ground of raging human expressions. The sanctimonious manifestation of a

thousand myriad imaginations, faiths, convictions. More so if there is a

tireless chronology of hundreds of years attached to it. Calcutta is one such

city. The Black Hole tragedy, the Bargis attacking the ‘infant’ British

settlement, the thrice-sacking of Calcutta … the tales go on. Of late, I have been researching on these

stories, and have been fortunate to come across some deliciously appealing

ones. I have included them below (bereft of any critical notes for the reader

to judge by herself/himself), primary and secondary sources included, and it is

hoped that you will find them worth your while.

|

| Job Charnock's epitaph |

[1]

A tomb in the corner, with Octagon dome,

Hath of marble a slab in the wall deep

imbedded,

Which tells how in hope of redemption to come,

Two pilgrims of this world found here their

last home,

Calcutta’s brave founder — the Suttee he wedded.

[Anonymous, Job Charnock]

Any essay on Calcutta remains incomplete without the mention of

its valiant founding father, a being forever shrouded in mystery. This fact was contested by the Shobhabazar zamindars and the Armenians; nonetheless, the fiction and non-fiction

involving Charnock qualify for entertaining reads. Charnock was the more

fortunate counterpart of John Lang’s Francis Gay, credited with the foundation

of a city that considers him with reverence and enigma even today. Like his

adopted country, his life in India was more colourful and adventurous than his

English gentry life. Of note are his legendary Indianization and his weakness

for Indian women.

|

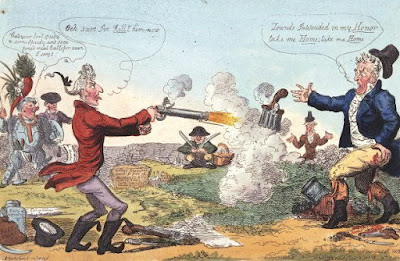

| A caricature of the Hastings-duel |

Charnock’s encounter with a half-breed named Mary Ann has seeded

into oblivion. The ten-year-old a ‘native’ slave of John Elliot, a proprietor

at Kasimbazar, was serving Charnock at an inn and in gratitude for his

acknowledgement of her English heritage, she had kissed him and became his

lover for one night. This would instil in Charnock a yearning for Indian women

and it would materialize in 1680 when he would rescue a suttee from a pyre,

re-baptise her as ‘Angela’, and marry her. Her memory would be cherished long

after her death by an anniversary sacrifice of a rooster on her tomb. She gave

birth to two daughters, Mary and Elizabeth. Following Emperor Aurangzeb’s

decree against prostitutes in Patna, Charnock would take as his concubine a

dark-complexioned harlot named Motia who had pasted abir on his forehead in a Holicelebration. Charnock reportedly had a

blissful marital life, but his associations haunted him politically and

socially. He was accused of nearly discarding his religion and proud heritage

for their sakes. Such is the power of love! [Taken from P. T. Nair, Job Charnock, The Founder Of

Calcutta: An Anthology]

|

| A second caricature of the Hastings-duel |

[2]

If any report different from what I have related should circulate,

and you should think them worthy of contradiction, I hope you will not scruple

to use this letter for that purpose. – Colonel Pearce in his letter to Lawrence Sullivan

On the morning of August 17, 1780, Calcutta stood witness to a

remarkable duel between the then Governor-General, Warren Hastings, and his

political rival in the Governing Council, Philip Francis. The latter had

questioned Hastings’ administrative and financial dealings, and the former had

written a scathing minute in an official meeting wherein Francis’ scandalous

liaison with Catherine Grand (one of the celebrated beauties of 18th century

Bengal) and his being fined 50,000 sicca rupees for adultery were mentioned. An

infumed Francis challenged Hastings to a duel, and the pair selected what is at

present called Duel Avenue at Alipore in Kolkata as the battle-field.

Duelling is a waging of war by gunfire to preserve the masculine honour, a

European ‘sport’ that has its origin in the Dark Ages. Each combatant is placed

at 14 paces from each other, accompanied by a Second, and they are instructed

to fire at each other on the count of three. Hastings’ Second was Colonel

Pearce, the Commandant of Artillery and Francis’ Second was Colonel Watson, the Chief Engineer at Fort

William. The duel commenced as planned; fortunately, none of the competitors

were no marksmen. Though Hastings managed to shoot Francis, he survived the

attempt and returned to England hereafter. The strains of the duel remained,

and haunted Hastings during his impeachment trial.

|

| Hastings House [From Kathleen Blechynden, Calcutta: Past & Present] |

If you wander through the streets of Alipore and find yourself in

an antiquarian store, you would unconditionally and endearingly hear of Lord

Warren Hastings. Even today, the shots from

Hastings’ and Philip Francis’ pistols echo through the air, inspiring stories

of all hues. People there know, with filial certainty, the haloed ground where

the legendary duel took place over two-hundred years ago. The events are recounted

with utmost precision, to the extent of passing as contemporary gossip. The

imagination stops not there but extends to the palatial Hastings House where it

is said, late at night, Hastings drives up to the house in his carriage,

scampers through the front door, and frantically searches for something in the

room that was once his study. Myths say that his spectre returns to secure the

lost papers that would have deemed him innocent at his trial of impeachment.

Typical British! Worried about his reputation from beyond the grave! [Taken

from Kathleen Blechynden, Calcutta: Past And Present]

|

| Pattle's epitaph |

[3]

Oh, the old Pattles! They’re always bursting

out of their casks. – Virginia Woolf

James and Adeline Pattle’s graves are one of the many forgotten

graves at St. John’s Church in Calcutta, but little does one know that the

elaborate tombstones stand over empty graves. More elusive is the sensational

circumstances in which ‘the biggest liar in India’ and his wife met their

deaths in that distant 1845. Hear it from Virginia Woolf herself, one of the

descendants of this infamous judge:

Julia Margaret Cameron, the third daughter of Janies Pattle of the

Bengal Civil Service, was born on June 11, 1815. Her father was a gentleman of

marked, but doubtful, reputation, who after living a riotous life and earning

the title of ‘the biggest liar in India’, finally drank himself to death and

was consigned to a cask of rum to await shipment to England. The cask was stood

outside the widow’s bedroom door. In the middle of the night, she heard a

violent explosion, rushed out, and found her husband, having burst the lid off

the coffin, bolt upright, menancing her life in death as he had menanced her in

life. ‘The shock sent her off her head then and there, poor thing, and she died

raving.’ It is the father of Miss Ethel Smyth who tells the story (Impressions That Remained), and he goes on to say that, after ‘Jim Blazes’

had been nailed down again and shipped off, the soldiers drank the liquor in

which the body was preserved, ‘and, by Jove, the rum ran out and got alight and

set the ship on fire! And while they were trying to extinguish the flames, she

ran on a rock, blew up, and drifted ashore just below Hooghly. And what do you

think the sailors said? ‘Pattle had been such a scamp that the devil wouldn’t

let him go out of India. – Virginia Woolf, Julia Margaret Cameron

Woolf’s colonial roots have spilt from her pen and many of her

works speak of her lesser-known legacy. Even the guides at the churches don’t

deem these two worthies of mention. But their great-great-great-grandchildren,

one of them William Dalrymple still visit them. It counts once in a while to

remember a notorious ancestor who made for good bedtime stories! [Taken from

Virginia Woolf, The Complete Works]

|

| The dissent of the natives of Calcutta [From Bidisha Chakraborty and Sarmistha De, Calcutta In The Nineteenth Century: An Archival Exploration] |

[4]

Quit the city O Mother dear

Don’t ever again come back here.

The woes of Calcutta grow day by day,

So it’s better Ma, that you keep away.

Here learned Justices pass judgements prime,

While city roads lie steeped in grime.

For fear of all the roadway dust

Our mouths and eyes we all keep shut.

Crapping and piddling in public places

Are now treated as grievous offences.

[Kaliprasanna Sinha, Hootum Penchar Naksha]

Kaliprasanna Sinha’s Hootum Penchar Naksha is unparalleled in its social portrayal of the Bengali festivities

and sensibilities. The satirical accounts of the Autumn festival and the Churuck Puja (celebrations indigenous to the city) are particularly lavish

and whelming, boasting of a lengthy history of continuity. But, did you know that the colonial Government

sought to interfere in these time-tested traditions only to meet with fierce

resistance from the legendary likes of Rani Rashmoni and the aristocrats of

Calcutta? Or that the Churuck festival, celebrated with so much aplomb even

today, almost bought a ticket to oblivion?

The Autumn festival was not only the time for the worship of

Goddess Durga, but also one of emblazoning culture in the form of nautch

performances, kobigaan, and British bhakti. Indeed, the denizens of the

city worshipped their Bengali Mother and their British Master. Nonetheless, the

authorities did not think dearly of the noisy ‘raptures’ caused by these

festivities. ‘On June 27, 1849, a notice was published in the Calcutta Exchange And Gazette, imposing certain restrictions on the routes of

the Bijoya Dashami procession in the main thoroughfares of

Calcutta, especially in the European quarters of the town’. The first voice of

protest was that of Rani Rashmoni of Janbazar, and she was joined by a large

number of native residents. Mathura Mohan Biswas spearheaded the signing of a

collective memorial, and it was forwarded to the government on August 28, 1849.

Some extracts from the memorial are provided below:

… the several Hindoo religious Ceremonies, which are performed at

these periods and that this liberal concession to their (British) creed and

their feeling is directly opposed to the present interference with their most

sacred Ceremonials.

… to conclude each Poojah by taking the images of their Deities in

solemn procession from the Takor Barees to the Banks of the River and cast them

into waters, and that without their last sacred act the whole rite would be

imperfect.

That from the 18th of July 1749 to the present time a century has

elapsed, and during that period the Capital of India has been under the rule of

ten Governors and eighteen Governors-Generals. Your memorialists might go back

to an era “to which the memory of man runneth not to the contrary”, but a usage

prevailing for a century to years and sanctioned by so many Rulers, needs no

further support.

|

| The Rashmoni Memorial [ From Bidisha Chakraborty and Sarmistha De, Calcutta In The Nineteenth Century: An Archival Exploration] |

It

is on these general grounds that your memorialists respectfully remonstrate

against a Regulation which interferes with so many of their body in the

exercise of Religious Rites, held so sacred and so long enjoyed.

The Under-Secretary of the Government of Bengal, I.W. Dalrymple,

promptly responded to the memorial, and the regulations were swept aside with

an assurance of ‘preventing any material inconvenience in the quarters through

which the Processions may pass’. Yet, not always did the indigenous crowd

harbour a penchant for all things traditional.

The city was filled with the sound of drums. The swingers were

itching to have their backs pierced with hooks … They had ghungroos around their ankles, gaudy chains around their waists, dyed gamchas of Tarakeshwar in their hands, garlands of bel leaves around their

necks, and topis laced with gold thread on their heads. – Kaliprasanna Sinha, Hootum Penchar Naksha

The Churuck festival almost lapsed to the abhorrence of

the upper classes. Largely deemed a carnival of the lower orders residing in ‘Calcutta’s

black town neighbourhoods of Kansaripara, Jelepara, Ahiritola’, it was when

they ‘came out on the streets to lampoon’ the ‘upstart Bengali babus, the

hypocrite Brahmins, the arrogant English sahibs, and the municipal commissioners

for failing to solve the civic problems of the citizens’. The educated elite

apparently found the swinging from the hooks and banphora (piercing hooks through flesh)

barbaric, unethical, and unsuited for an emerging Imperial city as Calcutta.

The applications came from the affluent ‘targets of the festival’ and were

backed by the Government. In earlier instances, Calcutta proved to be a soft

ground where laws could be easily enacted; in this case, not so much. One

‘Juggernauth Dutt of Badool Bagaun’ and one ‘Rampersaud Koondoo of Beltullah’

swung from hooks at the Churuck posts in the suburbs, defying authority. It

was said, much to the elitist disappointment, the celebration occurred unabated

and undiluted by the hypocritic elite’s reformist compulsions and wrathful dispositions.

[Taken from Kaliprasanna Sinha, Hootum Penchar Naksha; Bidisha Chakraborty and

Sarmistha De, Calcutta In The

Nineteenth Century: An Archival Exploration]

|

| .The Churuck Festival [From Bidisha Chakraborty and Sarmistha De, Calcutta In The Nineteenth Century: An Archival Exploration] |

[5]

… ‘Be warned’ says the author to his male

readers

The women of inferior households invariably

ignore their husbands;

Indulged beyond repair, their confidence is

increased.

[As we have seen in the case of the

fisherwoman insulting her husband…]

It is not a good idea to pamper your woman;

Irrespective of high and low families

[J. Shil, Machher Basante Jele Mechhonir Khed]

Judging from 19th-century popular songs and tracts in pamphlets,

it seems that the recent meat scandal is another of those frothy food scandals

that Calcutta is no stranger to! In 1875, the city was afflicted with worm-ridden

fish and the pamphleteers ‘relied on similar tropes of cosmic intervention to

right a reversed world order’. Though wiser reportings pointed at the scanty

rainfall over the past few years in causing the fishes to pick up diseases from

the dried-up, unclean river beds, the readership ‘firmly believed that the

catastrophe had been brought upon the city people by their own wrong-doing.’

‘Cast variously as a curse resulting from the insult by a group of fishermen to

the smallpox goddess, Sitala, and the challenging of Kali by the river Ganga,

the virulent spread of disease amongst fish in the riverine tracts of western

Bengal and Hooghly was seen as causing untold misery amongst the fish-loving

Bengali.’

Suddenly, a fisherman came along with a big carp weighing about

ten to twelve seers. Thebabu was elated to see the fish. He

decided that he’d buy it, whatever the price. He asked the fisherman, ‘How much

will you sell the fish for?’ The fisherman replied, ‘Huzoor, the price is

twenty hard slipper-strokes.’ The babu was hell-bent on buying the

fish, so he agreed to beat the fisherman with a slipper. – Kaliprasanna Sinha, Hootum Penchar Naksha

What was greater than the scandal was its consequences. The

calamity affected all, the rich and the poor. The media readily drew a touching

image of ‘a beleaguered Bengali population’ sharing in the misfortune and

‘trying to cope with the absence of fish, that vital ingredient in Bengali

cuisine and celebrated by poets and litterateurs ad infinitum’. ‘The weakening

of constitution and vitality resulting from a long-term deficiency of fish in

household diets, it was thought, would have a disastrous effect on Bengalis as

a race. Reduced to a meal of rice, lentils, and vegetables, Machher Basante Jele Mechhonir Khed feared, Bengalis would turn into Hindustanis or khottas, both offensive terms describing the supposedly

inferior Hindi-speaking up-country migrants in the city. Not surprisingly, the

widows rejoiced, for they had been barred from consuming fish by religion and

now, others by the sheer force of circumstances were forced to share their

dietary deprivation. ‘Buried in the narratives was also a veiled dislike for

the usually East Bengali migrant fisherfolk, who were depicted as involved in

malpractices and artificially inflating the price of fish even in the best of

times’. Evidently, women bore the brunt of ‘sin, guilt, and atonement’ in the

event. ‘Bengalis could be delivered from the disaster if their married women in

every household could fast for a day, chant from the current tract, worship

Sitala, and forego fish for a period of three months’. It was thought that the

insatiable demands of the aggressive fisherwomen concocted the undergoing

debacle, for, without their aggressive demands, the fishermen would not have

indulged in malpractices and brought the reprisal upon themselves. Contemporary

literature like Bishom Dhokha, Macchhe Poka and Macchher Basanta endorsed the convictions. [Taken from Anindita Ghosh, Claiming The City: Protest, Crime, And Scandal

In Colonial Calcutta]

|

| The cat and the fish ['Bhijhe Beral' or the Bengali babu] |

[6]

If they wish to they (the British) can even

build a staircase to the heavens,

We have already seen how they can make men fly

in balloons in the sky.

Now only if they could bring back the dead to

life

(I am sure) all would accept them as Gods on

earth.

[Nandalal Ray, Nutan Poler Tappa]

Indeed, only Gods could build something so spectacular as the

‘hanging’ old Howrah Bridge. It was something unheard of and unseen in so

‘primitive’ a city, and songs sprung up in the honour of ‘the floating iron on

water’. Besides the building of the wooden

bridge, what is of significance is its presence in the cultural imagination and

subsequently, in the popular memory:

Oh, what a pole has been built by the sahib

company!

How could a bridge be built over the Ganges?

Even Vishwakarma has admitted defeat …

Such intelligence and skill … there is no

problem anymore

All can easily cross the river now

The bridge has brought happiness upon this

earth

[Nandalal Ray, Nutan Poler Tappa]

Here

is another:

Wrapped in copper sheets and shaped as a boat

The bridge is afloat on the river

Iron chains running below secure it onto

anchors

Arranged diagonally on a series of boats are a

collection of mighty supports

Resembling the mythical moonbeam-drinking

bird.

The actual bridge rests on the structure

Itself a fine weave of beams and rafters.

There are attractive footpaths on both sides

Lined with charming railings.

[Aminchandra Datta, Howrah Ghater Poler Kobi]

[Taken from Anindita Ghosh, Claiming The City: Protest, Crime, And Scandal In Colonial

Calcutta]

The above tales may be extremely simple, lacking the appeal of

epic mysteries. I have had the need to present them in their raw forms for the

readers to be familiar with the minutest sensibilities that Calcutta is made

of. We encounter blatant ‘Oriental’ sexuality in Charnock, malicious rivalry in

Hastings, divine vengeance in Pattle, unconditional piety for traditions in

Rani Rashmoni’s memorial, cultural conflicts in the Fish Scandal, and racial

worship in the Howrah Bridge. The tales are fundamental in understanding where

we, Bengalis, stand as an ethnic race. And yes, we are forever hinged between

the East and the West, thanks to our ancestors. Calcutta, in a way, smoothens

this understanding of acceptability and rejection. The city is perfectly

unfinished, beautifully Plebian. It is so the city of the common man, and this

is what makes it special. We have no qualms in relating to it. We lose nothing

when we seek to interpret it. Maybe, after all, truth is not as strange as

fiction!

|

| The old, wooden Howrah Bridge |

No comments:

Post a Comment